( B-24 co-pilot 567th B.S., 389th B.G. )

PLOESTI

| Training/Practice |

| Preparations/Briefing |

| Mission Route |

| Target (Pitesti, Campina, Steaua Romana) |

| Bucharest, Izmir, Nicosia |

| Return to Berka 4 |

| CHAPTER TWO |

| CHAPTER FOUR |

PLOESTI (1 August, 1943)

(Note: The 1 August, 1943 attack on the oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania became the best known bombing mission of World War II. This action has been analyzed and documented on many occasions. The mission has always been the subject of much controversy and there are nearly as many variations as there are authors of various books and reports.

Several different oil refinery targets were attacked and each of the five bomb groups did their jobs with varying degrees of competence and success. The mission, as described in this history, is from the narrow viewpoint of my personal experience as a member of the 389th Bomb Group. It is most satisfying to realize that this group, although the newest and least experienced, is universally recognized as doing the best job.

I have many vivid memories of this exciting and, at times, terrifying mission. My research included all of the original 389th Bomb Group documentation available in the archives. In virtually every instance, the memories and documentation matched. A difference was the number of airplanes in our small formation which flew towards Turkey after the strike. I remembered two airplanes while the records showed four. I accept the documentation.

The radio operator of another airplane told a story recorded in several places. He described a formation position on the way to Turkey for their airplane identical to my memory of our airplane's location. During a recent meeting, the radio operator graciously agreed to discuss his views with me. He stated he was watching the target through the open bomb bay doors and then climbed up to the flight deck and looked out the pilot's and copilot's windows. He readily agreed that I was in the better position to observe the flying of the airplanes. His story is just as valid if their airplane was in a different formation position. I appreciate his thoughtful consideration of this matter.

The accepted spelling of place names has changed over the years. The mission documentation uses "Roumania" while "Rumania" is used in other places. The accepted current spelling of "Romania" is used in this history. Place names have also changed. The names existing in 1943 are used with modern names in brackets to assist the reader in using current maps.)

| TOP |

Training/Practice:

The speculation that we were in Africa for some special

mission was resolved the day after we returned from the mission to Rome. We learned that five crews were being transferred to the 98th Bomb Group

and that our airplanes would be modified for bombing at low altitude by

the installation of special bombsights.

The crews temporarily transferred to the 98th Bomb Group at Lete were those of Lt. Smith, Lt. Ellis, Lt. Opsata, Lt. Salyer and Lt. Fravega. The 98th Bomb Group had more airplanes than available crews while the 389th Bomb Group had extra crews. (During research, it became apparent that Lt. Fravega's crew flew the difficult Ploesti raid as their first mission. This was the only mission they flew from Africa.)

A team arrived at Berka 4 to install the special bombsights. The Norden bombsights were carefully removed and stored. A very simple gun sight, Model N-7, used in A-20 aircraft was installed in each of the airplanes in the group. This sight consisted primarily of a combining glass adjusted to an angle by means of a knob. The sight, normally used by the A--20 pilot, had an orange reticle collimated at infinity which was projected on the glass. The reticle appeared to be located at the target, allowing the pilot to move his head during use. The sight provided aiming for the A-20 guns and, through use of the angle adjustment, for the bombs.

The application in our airplanes was for the pilot to visually fly a course over the target and the bombardier, using the sight, was expected to adjust the angle of the glass, based on speed and altitude, and then release the bombs when the target appeared to pass through the reticle.

A few airplanes, not including "Blonds Away", were modified to incorporate a single fifty caliber machine gun in the nose, installed to point down fifteen degrees from straight ahead. A switch to operate the gun was provided for the copilot. The gun had an ammunition can which held seventy-five incendiary rounds and was intended to fire until the ammunition was expended.

The 391 gallon tank was retained in the left front bomb bay. The bomb bay tank was installed before the group left England and was never removed during the time in Africa. We expected a long mission at low altitude. The most plausible rumor was still some target in the eastern part of Germany with a return to England.

A small number of leaders from each of the five groups attended a briefing on Tuesday, 20 July 1943. Bill Nading attended this briefing. They were told about the target and the necessity to achieve maximum destruction on just one mission. The meeting was held in secrecy although it was obvious that an important briefing had occurred and it related to a low-level mission.

There were lots of discussions on Wednesday about the idea of attacking a tearget at low altitude with the B-24 which had been designed to bomb from high altitude. We started to call the technique of bombing at low altitude "skip bombing." Crew members had heard of the use of airplanes like B-25s with the bomb being dropped at low altitude just before the target so it would "skip" into the side of a target like a ship. Some people even speculated that the target might be ships.

Apparently, some crews in other groups complained about the unusual role being planned for the B--24s. Some reports even hint that morale was low. Most pilots had, at one time or another, buzzed and knew the thrill of flying just off the ground. Bill Nading and I talked about skip bombing and we felt enthusiastic about the prospects of bombing from low altitude.

Low altitude training was scheduled for Thursday, 22 July 1943. We were given a navigation mission and an assignment to drop practice bombs against a small target constructed of empty fuel drums (probably fifty five gallon size, although there were many German fuel drums of about the same size in the Bengasi area). The fuel drums were stacked in a wall, three drums tall.

We were supposed to start our training mission flying several hundred feet high and gradually lower the altitude as we became confident. After a few minutes, we were flying as low as about twenty--five feet and enjoying every second of it. The bombing practice was conducted in a pattern following a road towards the oil drum target. Each airplane in turn would fly down the road and drop a single blue practice bomb. A controller near the target would assign altitudes of either twenty-five, fifty, seventy-five or one hundred feet. After two or three bombs, we were hitting the exact stack we selected and, if the pilot had accurate speed control, could occasionally hit the middle barrel in the stack used as the aiming point. Of course, the air was calm, the conditions were ideal and there was no opposition.

The training mission was three hours long and was some of the best flying we had ever experienced. We learned that one airplane in another group had dragged its belly on the ground, but managed to get back into the air. Our mission critique revealed that bombing results at twenty-five feet were about the same as at fifty feet and most pilots felt the increased risk at the lower altitude did not justify the danger.

The training continued the next day. We started to fly in three aircraft formations. We were assigned to fly on the right wing of Captain Mooney. He was a good pilot and easy to follow. Soon we were flying in tight formation at the same low altitude. We were instructed to spread out on the bomb run with the lead hitting the center and the wing men attacking the ends of our oil barrel target. I wanted to see how the bomb dropped so with Nading's approval, rode in the bomb bay for one run. The bomb released and stayed directly under the airplane while it hit the ground and skipped up toward the airplane as it crashed into a barrel. This training session lasted two hours.

We flew again on Saturday, 24 July 1943 for two and a half hours. By this time, we were flying in formations of six airplanes. The second three--airplane flight moved into a trail position on the bomb run followed by shallow turn to the left and then to the right so they crossed the target at an angle from the left. The enthusiasm for flying at low altitude and doing skip bombing was extremely high. All of us, occasionally, had sober moments when we thought of ground defenses and enemy fighters around the important target we were training to attack.

After the completion of Saturday's training, all the air crew officers were assembled for a classified briefing. The briefing started with a statement that the 389th Bomb Group had been assigned to attack a very important target and that the mission would be extremely dangerous. In fact, the target was considered so important that its destruction would be worth the loss if none of us came back. We were then told that the mission would be volunteer and there would be no retribution for those who refused to go. Everyone in the meeting volunteered (Note: Reports state that Lt. James' copilot refused to fly, but this did not appear in the meeting. Recently, a researcher stated that the Lighter crew aborted on the ground because they were afraid to fly the mission. I believe the abort of the Lighter crew was caused by a failure in the aircraft. Lt. Lighter was in good standing after the mission. He flew the difficult Wiener Neustadt mission. He was missed by everyone when he was lost during the return to England.)

The importance and secrecy of the mission was then explained and we were cautioned to not reveal any information to the balance of the crew members or anyone else. The mission needed to be conducted with total surprise. Most of us were astonished when we learned that the target was in Romania, a country hardly ever mentioned in connection with the war. The broad picture was presented that Romania produced a substantial fraction of the oil and finished petroleum products used by Germany and Italy in the war and that destruction of the refineries would be a major blow. The overall strategy of the attack was for the principle refineries to be attacked simultaneously by formations from the five B-24 bomb groups then in Africa.

The 389th Bomb Group was assigned the Steaua Romana Refinery in the northeast portion of the village of Campina (Cimpina), about 20 miles northwest of Ploesti (Ploiesti) where the majority of the refineries were located. This refinery was presented as having a 1,750,000 ton per year capacity and produced 13% of Romania's total capability. Even more important was the cracking plant which produced 400,000 tons of higher quality fuel including aviation fuel for 17% of the total capacity of the country. The refinery was described as being the third largest European refinery.

A model of the refinery was then uncovered. This model, built at a scale of 1/500,000, presented the refinery in great detail including all the buildings, the blast wall between the refinery and the city of Campina, the tank farm north of the refinery and a general concept of the countryside and city near the target. In addition, we were shown eight-millimeter movies made by passing a camera at a scale altitude over the model. These movies gave the perspective and feel for the low altitude approach. Each crew was assigned a specific part of the refinery for a target. Our crew was assigned the cracking plant on the right side of the planned approach from the northwest.

We were told we should look at the model and watch the movies as much as we could until the mission occurred. The mission was planned for Saturday, 31 July which happened to be my twentieth birthday. The brief low altitude training in England and the intensive training in Africa now made sense to the air crews. It was a relief to know what was expected of us. The length of the mission was a shock, far longer than any of us had ever flown. The defenses, described as extensive, had been used in 1941 against a Russian attack. The element of surprise expected from the low altitude approach was to be the main protection against the defenses (Note: Some authors imply that the defenses were stronger than expected, but from my viewpoint, the defenses were not stronger, rather there was less surprise.).

The other crew members were anxious to hear about the mission. Since everyone in the airplane was subjected to the same hazards, it was hard to keep the secrets, but we were never aware of any violations of the rules in our group.

The next step in training occurred on Sunday, 25 July, when a mission was scheduled which included six-airplane formations and also five six-airplane formations flying in trail through maneuvers involving the entire group of thirty airplanes. Occasionally we could see formations of airplanes from the other four groups in the area. We visualized the large scope of effort in preparation for attack on the Ploesti oil refineries. We logged two and a half hours on this training exercise. The air crews were told we would not have any flying assignment the following day and should rest and be prepared for training on Tuesday.

The role of a copilot on some crews was very difficult and I continued to be grateful to Bill Nading, our pilot, for his effort in making me feel that flying the airplane was a shared responsibility. He assigned me to fly the airplane many times during the low altitude training. He surprised me on Monday morning, 26 July, by saying that our crew was going to fly its own practice mission. I never knew what excuse Nading used to get permission to fly an individual training flight.

When we got to the airplane, Bill informed me that I was the pilot and he planned to ride in the back;. He assigned Herb Newman, the bombardier, to ride in the copilot seat and was not to touch anything. I supervised the preflight of the airplane and when we were ready, started the engines and taxied to the end of the runway. The pilot in a B-24 cannot reach the ignition switches so I talked Herb through the copilots action in checking the magnetos. Then we completed our checklist, I lined up with the runway and made my first "solo" takeoff in a B--24. I don't know just what the other crew members thought about their nineteen year old copilot, but everyone seemed to accept the situation.

We flew around the area for a few minutes and then after going through the landing checklist, lined up with the runway for a long smooth approach and landing. Bill came on the interphone during the approach and told me I was doing just fine. After landing, I taxied the airplane to its parking place and shut down. The thirty minute flight seemed wonderful to me.

The training mission for Tuesday, 27 July, was described as a "special mission rehearsal" and the briefing was conducted as for a normal combat mission. The training plan was to assemble into the group formation and to depart the coast of Africa. The mission was then to turn back, following a specified flight path and altitude which simulated the final phase of the actual mission. The target was described as being built up from oil drums in the rough form of the oil refinery target. The oil drums were grouped to provide the locations of the boiler house, the distillery and the cracking plant. We instantly understood the layout from the model and movies which simulated a low altitude approach to the refinery. (Some written material suggests that actual buildings were constructed at some of the practice targets, but I remember patterns made up of oil drums.)

The training mission went well. It was a little hard to visualize the mountains of Romania as we descended over the flat Libyan desert. The navigators comments helped us picture flying down a valley with mountains on both sides as we approached the target. The 389th Bomb Group flew with the first twelve airplanes as one "division" and the remaining eighteen airplanes in a second "division". The first "division" had two sections of six airplanes formed in two elements of three airplanes each and the second "division" had three similar sections. Our assigned position was the number two position in the lead element of the third section in the second "division" (fifth section of the entire force). We were to be the last airplane to fly straight in at the right side of the target to attack the cracking plant. The trail element in each section swept out left or right as assigned and then converged on the same targets as the lead element. There were airplanes everywhere, but the practice went as planned and many of the blue practice bombs hit inside the target outline. We finished the 4.3 hour training flight with great confidence that the mission was possible and that we could destroy the oil refinery.

A similar, but shorter, training session lasting 2.5 hours was flown on Wednesday, 28 July, and the final practice mission, lasting 2.3 hours, was flown on Thursday, 29 July. (Some authors state that real bombs were dropped on the final practice mission, but I believe that all of our training missions dropped inert blue bombs.) The enlisted air crew members were briefed on the target prior to the Thursday training mission. This answered many questions which the enlisted men had as a result of the training sessions. They had been subjected to the same rigorous training as the balance of the crew and it did not make much sense to many of us to keep sixty percent of the crew members "in the dark" when we were all in the same airplane and subject to identical risk.

Friday was a quiet day. Many crew members wrote letters to their families. Part way through the day, word was passed that the mission was delayed until Sunday in an effort to gain increased surprise. The delay seemed intolerable as everyone was anxious to go and get the job done. I was a little embarrassed about my young age and I had not mentioned to anyone that Saturday was my birthday. I had planned to celebrate my birthday by bombing an oil refinery in far away Romania. Instead, I resigned myself to another low--pressure day in the desert. I went out to the airplane and talked to Guy Pannell, our crew chief, and felt satisfied that "Blonds Away" was ready for the mission, having been thoroughly inspected and serviced following the training schedule.

| TOP |

Preparations/Briefing:

A mission briefing was scheduled for Saturday, 31 July

1943, my twentieth birthday. Loading of the bombs was to be completed.

The first fifteen airplanes were assigned to carry three 1,000 pound bombs

each, with one hour delay fuses. The next nine airplanes were assigned

to carry six 500 pound bombs each, with one hour delay fuses. The

last six airplanes, including our airplane, "H-", were assigned six 500

pound bombs each, with forty-five second delay fuses. The pilots

of the last six airplanes were cautioned to close ranks as much as possible

as we approached the target since the bombs would be detonating soon after

we passed. Each nose fuse was armed after dropping by a small propeller

which would wind off in the slip stream. The propeller required 150

turns to arm the bomb and to insure the bombs were properly armed before

they hit the ground, the crews were instructed to turn the propellers on

each fuse seventy-five turns as part of the loading process. Nading

assigned the responsibility to me, causing a few moments of hard feeling

with Herb Newman, the bombardier. Herb and I agreed that we would

work together, he would install the fuses and I would do the winding as

instructed.

The detail mission plan called for the airplanes to be marshaled near the end of the runway late in the afternoon so that the fuel tanks could be topped off as needed. The fuel problem on the long mission required that airplanes take-off in as short a time period as possible. The ground personnel watered the runway all day and night. Even with the watering, the problem of blowing dust had been so severe on previous missions that it was concluded that each airplane would have its engines started just before take--off and we would make no engine checks. If there appeared to be a problem with the engines, the airplane was supposed to abort off the runway. It was also decided to take the airplanes off in flights of three with the two wing men starting their roll before they were engulfed in dust from the lead airplane. We believed this would place the wing men far enough behind that they could use full power without overrunning the leader.

We were required to be in our airplanes at 06:30 (local time, actually 3:30 AM, Greenwich Meridian Time) the next morning for a first airplane taxi time of 07:10 with a 07:15 take--off. Our airplane, nearly the last to depart, registered an actual take--off time of 07:44 showing that twenty-six airplanes were able to get off in just over thirty minutes, even with substantial periods for the dust to move out of the way between three airplane flights departing.

The route was to depart Africa from the coastal village of Tocra (Tukrah) at 08:30, then to a point over the Mediterranean (latitude 38 degrees 47 minutes north, longitude 19 degrees 44 minutes east), then climb to 10,000 feet en route to Corfu (Kerkira), then to a point east of Lake Prespa (Prespansk Jerzko) in Yugoslavia, then to Pirot, Yugoslavia where we would start a let--down to 7,500 feet, then to a point near the Danube River (latitude 43 degrees 50 minutes north, longitude 23 degrees 43 minutes east) and then to Pitesti, Romania. The 389th Bomb Group would then make a slight turn to the left towards the Transylvanian Alps and to a prominent monastery high on a ridge (Monasterea Dealulue) to be used as the IP where a sharp right turn would take the formation down a valley (wide canyon) with mountains on either side. The valley would lead to the oil refinery in Campina (Cimpina).

The gunners of the early airplanes were instructed not to shoot at the oil tanks which were mostly before the target. This was to reduce the amount of flames and smoke for the last airplanes. The gunners were instructed to save their ammunition for use against enemy fighters. The copilots of the few airplanes with the specially installed fixed gun were instructed to turn the gun switch on when crossing a road just before the target.

Each crew member was given an escape kit which contained a compass, a steel file, legal currency from several countries and some gold coins. One Type K--20 Aircraft Camera, a hand held, manually operated, eleven pound unit capable of taking fifty photographs was assigned to our crew to be used by the tail turret gunner, Joe Fussi, in an attempt to get photographs of the bombs exploding soon after the airplanes had left the target. Most of the bombs would explode about an hour after we left the target but the mission planners hoped to obtain confirmation that at least some of the forty-five second delay bombs were exploding in the target.

Most of the crew members went to their airplanes and finished loading bombs and ammunition. The airplanes were started and taxied into their marshaling position on the cross runway. The first three airplanes were positioned on the main runway, ready for take--off. The bombardier, Herb Newman, installed the fuses in the bombs. It was then my job to remove the safety pin and arming wire from the nose fuse and turn the propeller on each fuse through seventy--five revolutions on each of the six bombs, three in the right front bomb bay and three in the left rear bomb bay.

We then loaded several unauthorized incendiary bombs in the right rear bomb bay. Later, the 9th Air Force reported that 34 incendiary bombs were carried on the mission without definition of the specific airplanes. We may have loaded six 100 pound incendiary bombs. The crew gleefully talked about our extra contribution to the mission, sort of "everything and the kitchen sink." Bill Nading and I had already decided we were going to over boost the engines to fifty--two inches of mercury manifold pressure (forty--seven was normal) during the take-off roll and had no worry about the extra weight. The gunners also loaded a small amount of extra ammunition.

Some people in the 389th Bomb Group developed diarrhea over the previous ten days. Although everyone on our crew felt healthy, we took the improvised precaution of putting two wooden ammunition crates in the airplane, one filled with sand. This provided an empty box for anyone needing an emergency bathroom. The sand was to be used for esthetic reasons. If crews used these boxes, they usually threw them out as they approached Africa on the return flight. We never used our boxes.

Late in the evening, our crew chief, Guy Pannell, and I added a few more gallons of gasoline to the tanks. I jumped up and down on the wing to work a few more bubbles out of the gasoline. I was thinking about the length of the mission. Then we safetied the filler caps, I felt we had done all we could do to get Blonds Away ready for the mission. It was possible to see the setting sun sparkling from the Mediterranean when standing on the wing. My birthday had been busy and happy without any celebration. I looked at the sunset and wondered if we would return in time to enjoy the view by the next evening.

Some report spending a sleepless night. With my busy day, I went to sleep as soon as I crawled into bed after scattering the locusts from the outside of the mosquito netting and shaking my blankets to get rid of stray scorpions.

Research since the war shows that any expected surprise of the Ploesti defenses was lost even before the airplanes left Africa. The 9th Air Force spread a coded short message to Allied Forces with the intent that airfields and communication facilities in the eastern end of the Mediterranean would be on alert. The message was also picked up by a German Funkaufklarungsdienst unit near Athens, Greece. This unit had skilled cryptanalysts who reduced the message to plain text. A German officer, Lieutenant Christian Ochseschlager, distributed the message to all defense commands that bombers, believed to be Liberators, had been taking off since early morning in the Bengazi area. This message gave the antiaircraft defenses at Ploesti plenty of time to get ready.

The desert sun came up like a ball of fire. We ate breakfast and went to our airplanes. The first airplanes went down the runway and lifted off. Each flight of three airplanes left more and more dust as the runway dried out. The few available tank trucks had sprinkled the runway during the preceding day and all night.

| TOP |

Mission Route:

Finally, it was our turn. Captain Mooney lined up

in the center of the runway. He advanced his throttles and started

to roll. We applied power and ran alongside the dust trail from Mooney's

airplane. Blonds Away lifted off well before the end of the runway

and we were in position on Mooney' s right wing before the first turn.

The section led by Captain Mooney was assigned as the last in the 389th

Bomb Group. Since the 389th Bomb Group was assigned as the last group,

we had an opportunity to look ahead and see all of the airplanes on their

way to Ploesti.

Ahead of us to the north in the desert, we could see a column of oily black smoke. As we got closer, we could see the fire of an airplane which had crashed and was burning. The airplane was from the 98th Bomb Group and had crashed near their airfield at Lete. Even though we did not know the crew, we felt increased concern as the losses had already started.

Our group quickly assembled into a credible formation and we departed as planned. Some of the other groups were in loose formations and the entire force never achieved the planned organization. The speed and maneuvers varied from one group to another. We were glad the 389th Bomb Group leaders insisted on good formation flying.

The groups flew at 4,000 feet to the turning point at 38 degrees 47 minutes North Latitude, 19 degrees 44 minutes East Longitude, a point in the open ocean. At 11:19 local time (8:19 GMT) an airplane near the front of the task force was observed to explode and fall to the ocean, leaving a trail of smoke on the way down. We looked for enemy ships or aircraft, but could not see signs of hostile action.

We were in process of transferring fuel from the bomb bay tank. Safety procedures included turning off the intercom and other communication equipment and ventilating the aircraft by opening flight deck windows and opening the bomb bay doors a few inches. We imagined other airplanes were doing the same thing and wondered if the airplane which exploded in the front of the formation had a fuel transfer accident. (It turned out the airplane which exploded was Wongo Wongo, the lead airplane of the task force. Some have claimed mysterious motions of this aircraft before it went down. From our more distant view, it simply exploded and fell to the surface of the ocean. On a later flight, we had a fuel transfer accident where a quick disconnect hose used in the fuel transfer operation "popped" off and a large amount of fuel sprayed in the aft fuselage. We were thankful we had observed all precautions. I believe Wongo Wongo had a fuel transfer accident, nothing mysterious.) We could not help but think that a second airplane had been lost even before we reached enemy territory. (We also observed airplanes from other groups aborting. We watched one airplane jettison its bombs as it turned back. All twenty-nine airplanes in the 389th Bomb Group which took--off reached the target, but a number of airplanes aborted from the other groups.)

The formation climbed to 10,000 feet by the time we reached the coast of Albania north of Corfu (Kirkira). We could see large cumulus build-ups over the mountains ahead of us. Our leader elected to stay at the same altitude and easily threaded the formation past the clouds by making a few gentle turns. Some of the other groups climbed and circled with the result the overall task force was badly scattered beyond the clouds.

It was obvious to us that the five groups were not able to stay in the anticipated formation. We were concerned about the possible impact on the mission of having the groups arrive out of order and not at the same time. (There was no thought about the horrible navigation mistakes some of the groups would make later in the mission.) While we were feeling some concern about the lack of coordination our worries were increased when we observed two or three Bulgarian Avias, obsolete biplane fighters, flying just outside of our gun range, obviously tracking our formation.

We assumed the Avias were reporting our position to the German air defenses and the secrecy of the mission had been compromised. These airplanes took no hostile action. (These obsolete airplanes probably were flying near their maximum speed just to stay with the formation. It is unlikely they were equipped with radios and were no real threat to us.)

The countryside was peaceful. Our group gradually descended to 7,500 feet. We were excited to see the Danube and observed it was definitely not "blue". Charlie Weinberg, our navigator followed the ground track of our group and reported we were on the assigned course. We retained confidence our group would be able to carry out its assigned mission.

| TOP |

Target:

We reached Pitesti, Romania and made the necessary course

change to fly along the Transylvanian Alps. The tops of the mountains

to our left were shrouded in clouds. We observed the airplanes in

the lead making a right turn down a valley and our navigator said they

were turning too soon. We could not see the monastery we were to

use as our checkpoint and realized it may have been hidden in the clouds.

The 389th Bomb Group was in good formation as we made the turn. The

lead element of the formation then turned left and all the airplanes stayed

in position through a nearly 180 degree turn followed by a right turn.

By this time, the monastery was visible on the ridge to the north.

The leaders then turned right down the correct valley and we all breathed

a sigh of relief. (After the mission, Major Brooks, Command Pilot

in Ward's airplane, the lead of the second "division" of seventeen airplanes,

related his feelings when their crew knew the turn had been made down the

incorrect valley. He decided to stay in the good 389th Bomb Group

formation rather than "go on his own" even though he knew the initial turn

was down an incorrect valley. He was thankful he was in the correct

position when the lead "division" corrected their course.)

The flight down the valley was slightly downhill. Some of the other groups describe very high airspeeds, but our leaders flew at 200 miles--per-hour which was achieved with very little additional power. We changed our mixture controls to automatic rich and increased the propeller RPM to insure that maximum power would be available if needed. The practices of the 389th Bomb Group were especially helpful in the event airplanes were damaged.

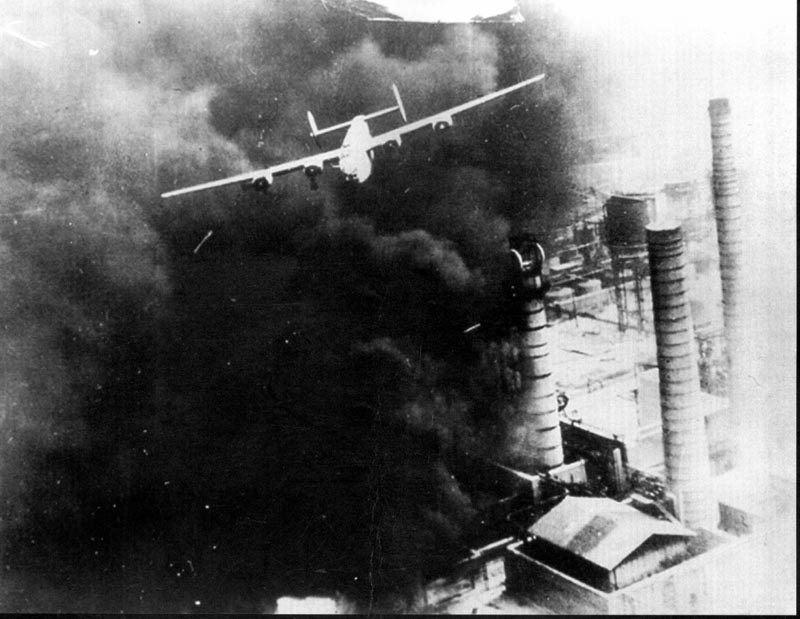

The target ahead of us looked just like the model and movies we had watched so many times during the previous few days. The trail elements in each section swept out about a mile and back in converging on their assigned targets just after the airplanes in the lead. From our position at the rear of the formation we could see the events unfold in front of us. The airplanes equipped with a single fixed machine gun loaded with incendiary bullets started some fires which produced heavy smoke. The enemy had many guns firing pointblank at the airplanes. Some of the early bombs hit installations, including the power house, which exploded or ignited even though the bombs had delay action fuses. It was like stirring up a bee's nest.

The airplanes going straight in were getting hit. The Hughes airplane (J), third directly ahead of us was on fire but kept going and dropped its bombs into the target. Horton's airplane (C-) directly ahead was getting hit after he released his bombs as he made a slight correction to the right to avoid smoke and flames. Bill Nading and I looked at each other and I concurred by a hand gesture with him to go through the smoke and flames. We were flying at an altitude about half way up the height of the chimney of the power plant, the target of the lead airplanes in each element. Our bombardier released the bombs and we zipped through the smoke and flames. We could see the flash from the barrels of guns shooting at us from pointblank range, but Blonds Away continued to fly normally. I assumed we were getting hit but could not detect any damage. Our tail gunner, Joe Fussi, reported that the tail turret had failed and he was trying to repair it. (Later examination showed this to be an equipment failure unrelated to the combat.)

We crossed the village of Campina flying just above the roofs of the houses. We could see Mooney's airplane (R-) wobbling along and we were trying to move into a tight formation with it. We caught up with Horton's airplane (C-) which appeared to be in bad shape with a major fire in the fuselage. Just as we were even with it, perhaps fifty feet higher and one hundred feet to the left, the airplane hit the vertical bank of a stream bed just beyond the village. The airplane crumpled into a fireball. It did not appear that anyone could survive this crash, but a few months later we learned the top turret gunner survived. We could see to the left the Hughes' airplane (J) sliding to a stop after cart wheeling into a stream bed. Some claimed they could see a crew member climbing out of the wreckage. We learned later that two crew members survived the crash but one soon died.

We slowed into position alongside Mooney's damaged airplane in our normal assigned right wing position. The propeller on the number two engine was being feathered as we watched. The airplane stayed close to the ground and appeared to be under control. A large stream of gasoline was pouring from the bomb bay. A man fell part way out of the bay, but managed to pull himself back into the airplane.

We observed a flight of four German Bf 109s climbing from left to right about a thousand feet above us, apparently headed toward airplanes farther to the west. We were happy they ignored us and were glad that Mooney' s airplane continued to fly a few feet off the ground, but headed south of our planned escape route. Our radio operator, Stan Brayovich, signaled their radio operator in Morse code using the Aldis lamp and soon was able to inform us that the pilot, Mooney, was dead and they didn't know exactly what to do. I knew that my fellow copilot, Hank Gerrits, was flying the airplane. Hank had his hands full and we could imagine the problems he was having. We could only guess at the extent of the damage and the fuel which had been lost, but we concluded to tell them to go to Turkey since we could not imagine they could make it back to Africa.

| TOP |

Escape:

The ground track followed by Mooney's aircraft took us

south, about fifteen miles west of Ploesti. We could see the fires

and smoke from the attack on the targets by the other four groups.

We could also see Bucharest in the distance. Soon after the target,

two other airplanes, Podolak (Z) and James (S), joined with this formation.

By this time we were many miles east of the route of the other airplanes

and knew it would be impossible to find and join with the remaining airplanes

of the 389th Bomb Group. We could not see leaving our element leader

with one propeller feathered and with other damage and a dead pilot to

find their way to Turkey. We decided to stay with the formation and

then try to return to Africa from Turkey.

We thought about moving into the lead position, but decided we could advise them and then adjust our speed to that of their damaged airplane. We decided the best place to go in Turkey was to the Turkish airfield Cumaovasi, ten miles south of Izmir. Our briefing material contained information on this facility. We crossed the Danube River into Bulgaria. We advised a small course change and the need to climb to cross the Balkan Mountains which have peaks just above 5,000 feet. We felt reluctant to leave the protection of flying close to the ground, but knew it would take the damaged airplane some distance to gain the necessary altitude. We received a few rounds of anti--aircraft fire as we approached the mountains. The ugly, black bursts were not even close to the airplanes. We did not see any enemy airplanes as we continued our journey.

We crossed into the very eastern end of Greece and then into Turkey. Turkey had been neutral, but biased toward the Germans and we did not know how we would be received when we entered their airspace, especially since our route would take us across the middle of the Dardanelles. As soon as we entered Turkey we saw several Turkish fighter airplanes. They flew near to us, but never exhibited any hostility at all. The Turkish airplanes included Spitfires, Hurricanes and Bf109s. These airplanes escorted us during the remainder of our flight to Izmir.

When we reached the airfield south of Izmir, we waved to Hank and the other crew members and signalled them to go down. We watched as Mooney's airplane (R-) and James' airplane (S) made successful landings. Hank actually landed their airplane in an open field near the airport. (Then Hank returned to England several months later, he told me it was the first time he had actually landed a B-24 by himself.)

Bill and I talked about what we would do when the damaged airplanes left the formation. We decided we would fly through the mountains in Turkey and try to reach Cyprus. We did not have enough fuel left to make a detour around German occupied Crete and we considered flying across that island as being dangerous.

All the Turkish airplanes followed the two damaged airplanes and did not interfere when we headed southeast. We stayed low as we flew through the tops of the mountains and soon considered we were beyond the range of the airplanes which had been tracking our little formation. Our navigator, Charlie Weinberg, did not have satisfactory maps of the area and the eastern part of the Mediterranean. I had an inexpensive atlas tucked behind the water jug which I used to plot up my trips. Charlie took this atlas and used it to select our headings. The map for Turkey had enough detail that we found our way to Yardamici Burnu, a prominent feature on the coast south of Antalya, Turkey. The sun was going down as we departed the coast.

We set up the airplane for maximum range, had the crew close the waist windows and retracted the deflectors (used to protect the waist gunners from the airstream). The crew threw the balance of the ammunition overboard. We asked Al Nix, the flight engineer, to insure that all the fuel had been transferred from the wing tip tanks and the bomb bay tank into the main tanks. Al called from the back of the airplane saying he spilled a "tablespoon full" of gasoline and felt like crying. As night descended on us, we turned the cockpit lights, ultra violet excitation, for the instruments to the lowest settings and let our eyes adapt to the darkness. The stress of the mission and the long day was apparent as we peacefully cruised through some rain showers in the dark.

As we reached the ETA (estimated time of arrival) for the coast of Cyprus we scanned the darkness ahead. I claimed I could see a "less dark" strip and wondered if it might be the beach and surf. We fired the colors of the day from our Very pistol and a welcome airfield lighted up in front of us. We turned to line up with the runway and made a normal landing even though our landing light did not operate. As soon as we were on the ground, the runway lights were switched off and we followed a jeep with a faint light to a parking area.

We observed many of what we supposed were British fighter airplanes parked on the airfield. We were surprised there were so many of them. We were the only B-24 on the field and had completed our mission in thirteen and a half hours. I opened the top hatch and with my flashlight walked to each wing tip and back along the fuselage to the tail and was surprised to discover that the airplane was undamaged. Then I climbed out of the airplane to the ground and checked the entire bottom of the airplane, again finding no damage. We had flown through the "guns of Ploesti" without a scratch.

We were surprised that only three or four British personnel came to meet us and see the airplane. We filed an arrival report and asked that a message be sent to our base. The RAF officer in charge of the airfield, Squadron Leader Buchanan, was anxious to have us leave the field and as soon as the airplane was secure, we climbed into a truck and were driven to downtown Nicosia where we were served a wonderful dinner in a hotel. We especially enjoyed ice cold watermelon after our month in the desert. Some trees along the road were in blossom and the wonderful fragrance seemed strange as we thought about the events of the day. We were then taken to a British army base and were housed in tents dispersed in an olive grove. A British sergeant was assigned to each of us and was right there to show us the facilities and make us as comfortable as possible. We were very tired and I went right to sleep and slept peacefully until daylight.

| TOP |

Return to Berka 4:

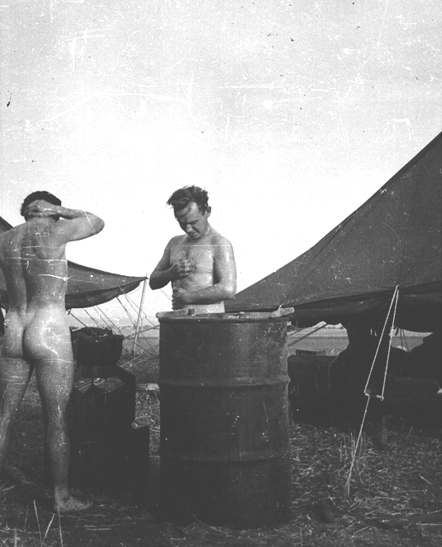

When we awakened, our sergeants were right there waiting

for us. They had shaving equipment, towels and soap for us.

It became apparent to us that these sergeants were providing us with their

own personal equipment and we likely used their beds. They apparently

were aware of the mission we had flown and considered it an honor to help

us. The British were surprised that we wanted to go back to our airplane

this early in the morning, but gave us some breakfast and provided a truck

to take us to the airfield. Along the way to the airfield we observed

people threshing, using a "sled" pulled by a donkey to shell the grain

and people with pitchforks tossing the straw and chaff into the air.

The early morning weather was beautiful.

We discovered that eight other B-24s had landed after we left the airfield. One of these made a crash landing due to a landing gear failure and the aircraft was lying on its belly alongside a runway. We were the only crew to arise at an early hour and go to the airfield. We were amazed to see that the British fighters we observed the evening before were "stick and canvas" dummies. A principle duty of the RAF at the airfield was to move the dummies around so German reconnaissance would be fooled. The only real British airplane we could see was a Walrus, a large single engine biplane amphibian for air-sea rescue.

The RAF ground personnel asked what they could do to help us. We asked for two thousand gallons of fuel. One of the officers thought this was funny and explained we could have as much fuel as we wanted but we would need to help as the fuel was buried in the ground in five gallon cans. They produced shovels and a light truck and we started. Bill Nading and I talked about the situation and we decided to go to Lydda, Palestine, reported as having better facilities. We loaded 300 gallons which with our remaining fuel gave us plenty for the short trip.

Blonds Away checked out perfectly on our preflight with the exception of the tail turret and the landing light. We were soon in the air noting we were still the only Americans on the base. We crossed the island of Cyprus, departing to the southeast, and about an hour later could see the coast of Palestine. We identified the harbor at Haifa and were soon at Lydda (the present location of Ben Gurion airport at Tel Aviv, Israel).

The watch office personnel were excited to have a Ploesti airplane show up. We realized the raid was the main news item. We thought we could easily obtain 2,000 gallons of fuel at this larger airport but soon learned that most airplanes using this base were small and the fueling trucks were also small. They assigned four fueling trucks and started pumping fuel through "garden hose" sized lines. After getting a few hundred gallons of fuel we decided to go to Cairo where an American base was understood to be in operation.

After takeoff, we discussed the possibility of swinging over Jerusalem. We could see the hills to the east where Jerusalem is located. We decided we should stick to business and hoped we could have leave and visit Palestine some time in the future. We flew along the curved coastline of the southeast part of the Mediterranean. We were still in the mood for low altitude flight and dropped down after reaching the barren desert. It looked like the sand dunes went to the horizon. At one point, we saw an Arab riding on a camel.

Charlie Weinberg, the navigator, told us when we had progressed far enough along the coast to take a straight line to Cairo. We climbed to several thousand feet as we really did not know about the defenses of the Suez Canal. We crossed the canal which looked like a small ditch through the desert which extended from horizon to horizon. We could soon see Cairo ahead of us and were excited to spot the Nile River and the pyramids. We called on the radio frequency being monitored by the American base and were surprised to learn the base was not open to transient aircraft because of construction and that we should land at the British base at Heleopolis. This field had a suitable runway and was the repair depot for British Wellington bombers. We landed at the base and the personnel swarmed around our Ploesti aircraft. They provided the service we required in a few minutes. Since our field, Berka 4, had no regular night landing facilities and it was getting late in the afternoon, we decided to send a message to our base and finish our trip the next day.

The British officers recommended we stay at the Heleopolis House, a hotel in Heleopolis, a suburb northeast of Cairo proper. This hotel was the fanciest place I had ever been. We checked at the desk and found they were willing to cash in the gold coins from our escape kits. This was the only money we had. We felt out of place in our grungy flying clothes, but the people made us most welcome. The dining room apologized for the wartime food, but it tasted good and we were soon in bed.

We got up early in the morning and decided it would not make much difference when we reached our base so we decided to go to downtown Cairo. We rode on a streetcar to the vicinity of the famous Shepherd Hotel. We looked in a couple of stores and were trying to decide what else to do. A short older man dressed in a western suit asked us if we would like to go to the pyramids. We thought we were being hassled and told him "no". He persisted and said that he was a member of the staff of the Egyptian Museum and just wanted to be nice to us since we were members of the American bomber crew. Since we had our weapons with us we concluded it would be safe and reasonable.

The man whistled and a very nice car pulled up and we were soon on the way across the Nile River to the pyramids. He explained to us about the pyramids. We rode horses around the pyramids. (My horse was named "Asfoo 5" and in 1993 I met the son of the man who owned the horses.) The visit to the pyramids was most interesting, but we decided we needed to go back to our base in the afternoon. Our host then drove us to the British base in Heleopolis.

We preflighted our airplane and taxied to the main runway. This runway pointed directly at a large apartment building. Before we taxied, we noticed many people gathered on the balconies of this four or five story building, apparently to watch us depart. We knew we had more than enough distance to clear the building, but it looked very close as we advanced the throttle. It was exciting to fly over the building and look into the faces of the people watching us. We circled around the pyramids and departed across the Western Desert for our base.

When we reached Berka 4, we flew across the field, pulled up and circled to land. We noticed many people and vehicles headed toward our parking place and wondered why we were getting such a welcome. We soon learned that some people had only heard vague rumors about our status. We quickly decided to not say anything about our morning visit to the pyramids. Our crew chief, Guy Pannell, was especially happy to have us back and to learn our airplane had not been damaged at Ploesti. We were taken to the tent used for debriefing and the entire crew met with Major Mahar, our "Interrogator".

We described our observations of the mission. The interrogator was especially anxious to learn what he could as to our assessment of the damage to "red" target. He was very unhappy that our tail gunner, Joe Fussi, had only been able to take one picture with the K-20 camera which he had in the tail turret. The intelligence officer had little sympathy for the fact that our tail turret failed and Joe was trying to get it back in operation as we expected enemy fighter attacks. This picture survives in the Air Force photo archive maintained by the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.

Six airplanes out of the twenty-nine dispatched were lost. We saw the crashes of 42-40735 piloted by 1st Lt. Robert W. Horton and 42-40753 piloted by 2nd Lt. Lloyd H. Hughes (posthumous Medal of Honor). Two other airplanes were lost in Romania, 42-40768 flown by 1st Lt. Robert J. O'Reilly II and 42-40115 flown by 1st Lt. Melvin E. Neef. The two airplanes we escorted to Turkey were 42-40744 piloted by 1st Lt. Harold L. James and 42-40544 piloted by Capt. Robert C. Mooney until he was killed at the target and then by 2nd Lt. James F. Gerrits, the copilot. The entire force lost fifty-four airplanes out of the 178 dispatched. Fifty airplanes which returned were damaged.

We were glad to see that our personal belongings were protected and untouched in our tent. There were stories about people making raids on equipment when people were lost on combat missions.

We were happy to be back to our home in the desert.

| TOP |